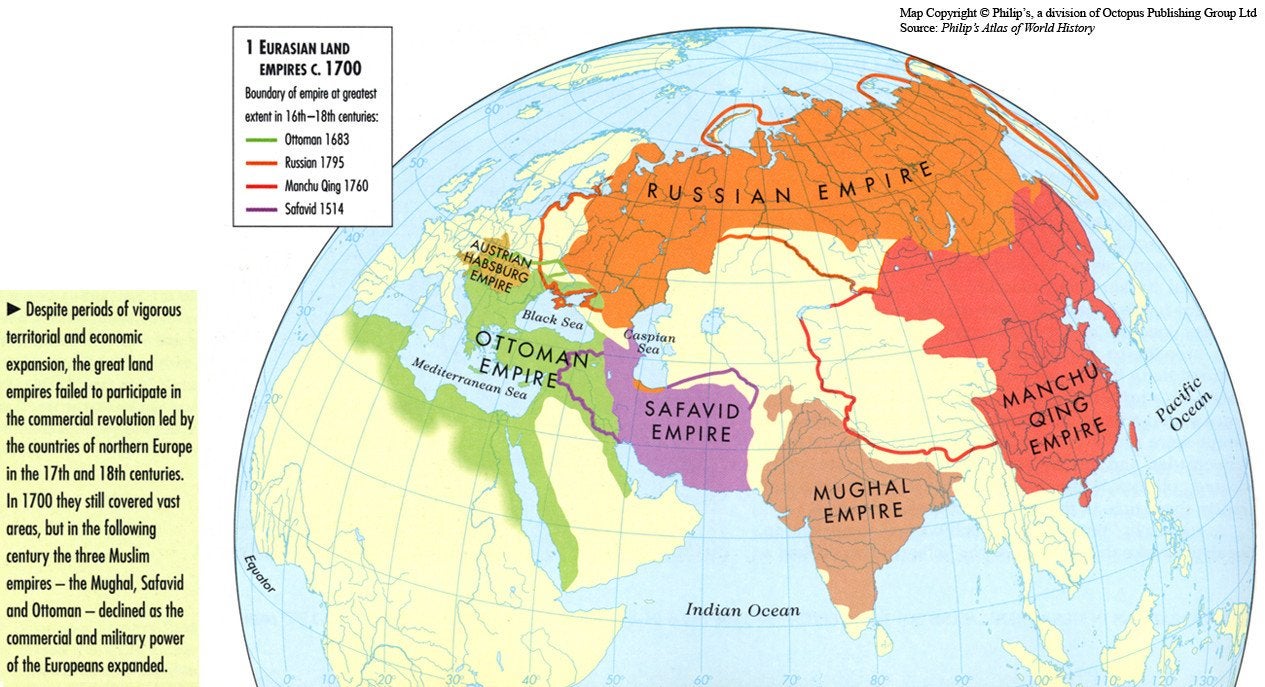

3.1 Expansion of Land-Based Empires

These empires formed like others, through the conquest of economically or strategically important areas. However, there are a few unique ways these empires were forged.

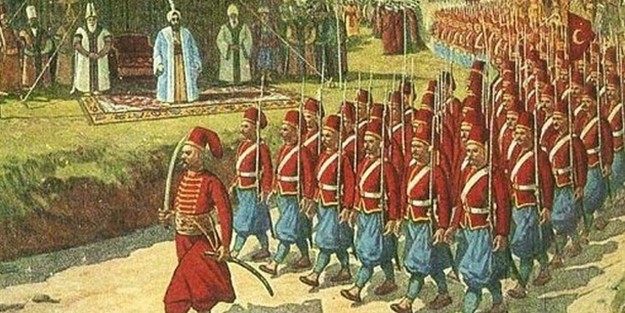

Many of these empires are also known as “Gunpowder Empires” because they were some of the first to use gunpowder armies on a large scale, several hundred years before Europe. In the early days of gunpowder weaponry, it was a highly technical craft: an empire needed a large, skilled population to cast the metal parts for weapons as well as a resource pool to manufacture gunpowder. Training soldiers in gunpowder weaponry also took time and money, money only a large empire possessed. The first gunpowder weapons were used by the Song Dynasty in China, but the Islamic Empires (Ottomans, Mughals and Safavids) and Qing China were the first to utilize them to a greater extent. The capture of Constantinople by the Ottomans and the conquest of Central Asia by the Qing in the late 1600s both owed their success to gunpowder weapons.

Another feature that helped a number of these empires rise to prominence was their friendly attitude towards merchants and reduction of existing taxes. The Ottomans and Mughals in particular are known for this. The Mughals, in the early days of their empire, abolished the jizya tax on non-Muslims (the majority of the population) and the Ottomans also had notably lower taxes than some of the empires they conquered, such as the Byzantines.

Many of these so-called Gunpowder Empires toppled existing empires who had weakened over time. Sometimes these were established empires like the Byzantines, toppled by the Ottomans, or Mali, which was subjugated by Songhai. Other times these were the descendants of nomadic conquerors, such as the Timurid Empire in Persia, conquered by the Safavids, or the Yuan Dynasty in China, overthrown by the future leaders of the Ming Dynasty.

Why empires weaken and fall is a complex process unique to each empire. Nomadic empires often weakened after their initial conquest because of their limited experience governing settled landed states or because they adapted so much to local customs and lost their fighting edge and distinctive identity. Also, with the rise of gunpowder weapons, nomads in particular lost their edge when horses were no longer the most important weapon on the battlefield.

3.2 Governments in Land-Based Empires

Some empires relied heavily on their military establishments to run the empire, and sometimes this even included bureaucratic work like paperwork and record-keeping.

|

|

Across many of the empires leaders built large monuments for various purposes. Sometimes they reinforced the rulers’ connection with established religions, sometimes they emphasized military power, other times they promoted trade, and occasionally they were just for personal flexing.

|

- In the Mughal Empire, a number of mausoleums (tombs) were built to reflect Traditional and Persian Islamic Architecture, so much so that Mughal Architecture became its own category of Islamic Architecture in South Asian history. The most well-known example is the Taj Mahal, built as a tomb for a Mughal Emperor’s wife; it has the appearance of a mosque (dome, minarets, etc.) and the interior is covered in excerpts from the Quran, the holy book of Islam. These all serve to reinforce the piety and faithfulness of Mughal rulers to Islam.

|

Sometimes buildings were not enough, and there are other examples of rulers using religion to promote their power, either directly or through their right to rule given by a divine power. The term divine right comes from European History, though the idea is not new. Since the end of the Roman Empire, many European monarchs from Russia to France claimed, and were claimed, to be ruling in the name of the Christian God. This did not mean the rulers were divine, but simply that they ruled by the consent of the divine, or with god’s permission.

- In Africa's Songhai Empire, the ruling family promoted Islam, as had their predecessors in Mali and Ghana. But, the Songhai rulers brought in more Islamic scholars and more forcefully spread the religion among the people of the empire (a change from the Mali rulers who did not force their subjects to convert). In an effort to get even more people to accept Islam, many of the rulers of the empire also took the name Muhammad, after the Islamic prophet, and local Islamic scholars spread a story that the empire’s founder Muḥammad I Askia was a jinn, a type of spirit in Islamic mythology, who protected the empire’s subjects.

- In the Aztec Empire (technically, a confederation of three cities) the rulers maintained a close relationship with the priest class. Aztec rulers launched campaigns to acquire prisoners of war and human tribute from subject people in order to continue the practice of human sacrifice by the priest class, which was demanded by the Gods. The Aztec Empire was a militant state which subjected most of the other peoples in Central Mexico in return for tribute in goods and people, calculated via tribute lists. In return for humans for sacrifice, Aztec priests legitimized the rule of the various Aztec leaders. It should be noted that this practice was not new in Pre-Columbian America, but the volume of the Aztecs’ sacrifices made them very unpopular among the people of Central Mexico.

Because all empires need money to run, one of the major elements of an empire, really any modern state, is some system by which to collect funds, either in money or some other form of value, and then distribute them.

Sometimes there were particular classes of people within an empire who were tasked with collecting taxes. For example, the salaried samurai in Japan and the zamindars in the Mughal Empire were military leaders or military classes in the empire, but they were also given the task of collecting taxes for the central government. The reasons for this varied, for example in the Mughal Empire, the ruling Muslims gave local Hindu princes the task of collecting taxes as zamindars in order to incorporate them into the government.

Other times governments sold the rights to collect taxes in a practice known as tax farming. This was most famously practiced in the Ottoman Empire, where the Sultan would give a non-government official the right to collect taxes for themselves at their own rate from a certain number of villages for a given amount of time, in return for an upfront payment. This was a quick way for the empire to raise funds, but could stifle development in the long run as the tax farmer could eliminate any surplus production by taxing the people too much. Taxes could also be collected in many forms. In pre-modern times, when metal currency was not widely available and paper money was not in fashion, taxes could be collected in the form of labor or products (referred to as a “tax in kind). However in the Ming Empire, when Spanish colonization of the Americas led to an abundance of silver coinage flowing through the empire, the government made the decision to collect all taxes in silver. This monetized the economy, since labor is not easily mobile and food tribute rots eventually, but silver is solid. This made it easier for the government to pay for services and support the bureaucracy, though eventually inflation became a problem as the supply of silver continued to increase.

3.3 Belief Systems of Land-Based Empires

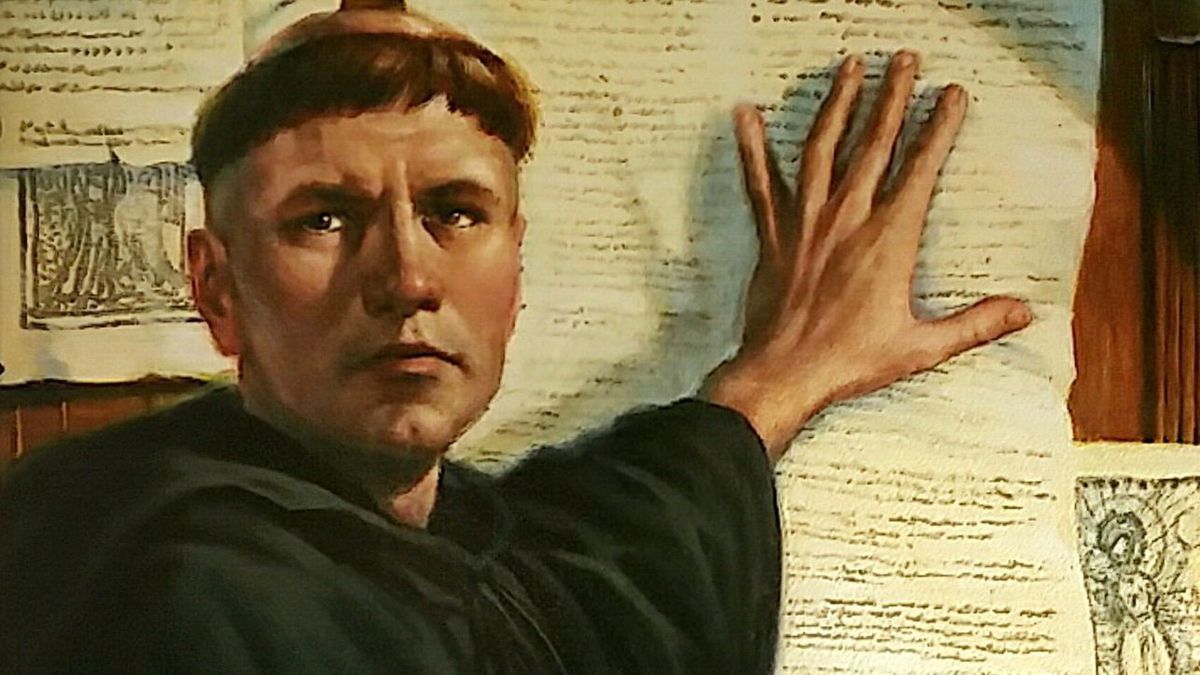

One significaant feature about these empires is that a number of them were the catalyst, if not outright cause, of several new or modified religious movements. These changes were sometimes used or supported by rulers, often to enhance their prestige.

|

In Europe, the newly created Protestant movement within Christianity, which opposed the Catholic Church in Rome, found strong supporters in Northern Europe and in parts of France. Rulers such as Henry IV in France or Albert Duke of Prussia promoted or tolerated Protestant ideas that might have otherwise been crushed by the Catholic Counter Reformation and Inquisition, which received support from Catholic monarchs. But like their Catholic counterparts, Protestant monarchs used the newly formed Protestant churches to break away from the church in Rome and seize its property.

|

In South Asia, the Mughal Empire held a much deeper connection between Islam and Hinduism than had previously existed. Muslims had been in South Asia since the beginning of Islam, but now a Muslim power controlled almost the entire continent. These deeper interactions between the ruling faith and the majority faith led to, and were a result of, popular religious movements such as Sufism and the Bhakti Movement.

|

Additionally, a brand new syncretic religion known as Sikhism emerged in northern South Asia, containing many elements of Islam (monotheism) and Hinduism (reincarnation and karma). It is not a coincidence that Sikhism emerged in northern South Asia where Islamic-Hindu contacts were strongest.

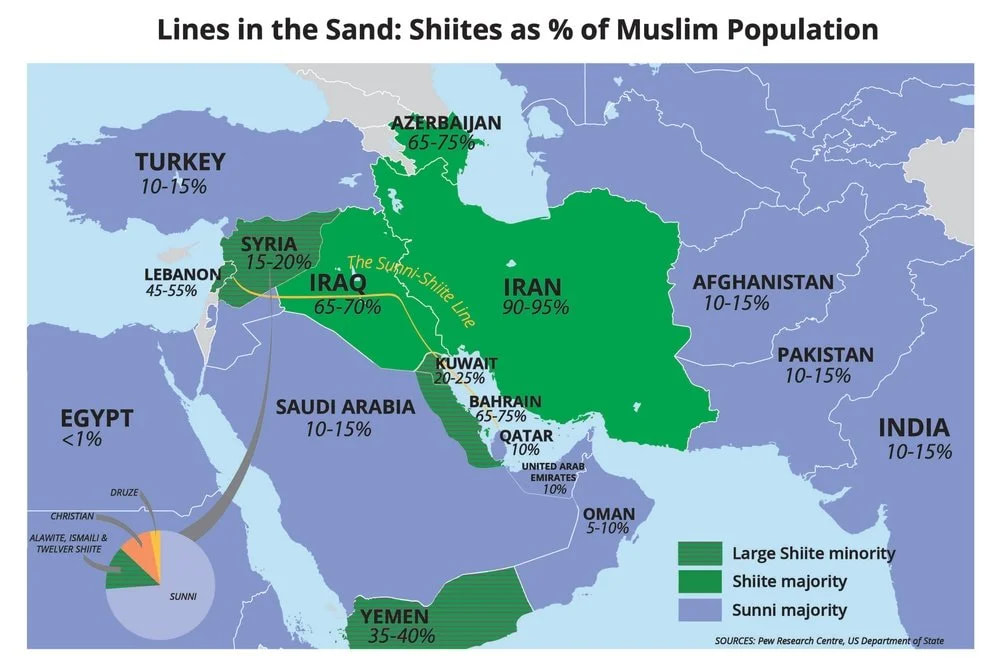

In the broader Islamic World, the political competition between the Ottomans and Safavids over territory and trade intensified the division between Sunni and Shia Muslims. The Sunni-Shia split occurred around 700 CE, long before either empire, but the conflict between them intensified, especially once the Sunni Ottoman Sultan claimed the title of Caliph, leader of the Muslim world, and the Shia Safavid Shahs also claimed divine connection via the Imams (leaders) of the Shia community.

|

In the Americas, both the Aztec and Inca Empires continued earlier religious traditions that had developed in those regions. The Aztec religious pantheon included several Mayan deities and the Aztecs used the Mayan script as well. The Incas continued the religious practices of the Moche who came before them (and the Chavin before them influenced the Moche), specifically that of worshipping the sun and moon, though in the Moche tradition the moon was more powerful. Both the Aztecs and Incas practiced human sacrifice, as did almost every Pre-1492 American Culture before them, though the Aztecs in particular practiced it to a much greater degree.