Foundations of World History, or The World Before 1200, is a combination of Periods 1 and 2 from the old AP World History model. It covers approximately 10,000 BCE to 600 CE. This unit will help us in laying a foundation for the updated material from 1200 CE to the Present that will be tested.

The information below is from the original course key concepts that made up the eras 8000 BCE to 600 CE.

The information below is from the original course key concepts that made up the eras 8000 BCE to 600 CE.

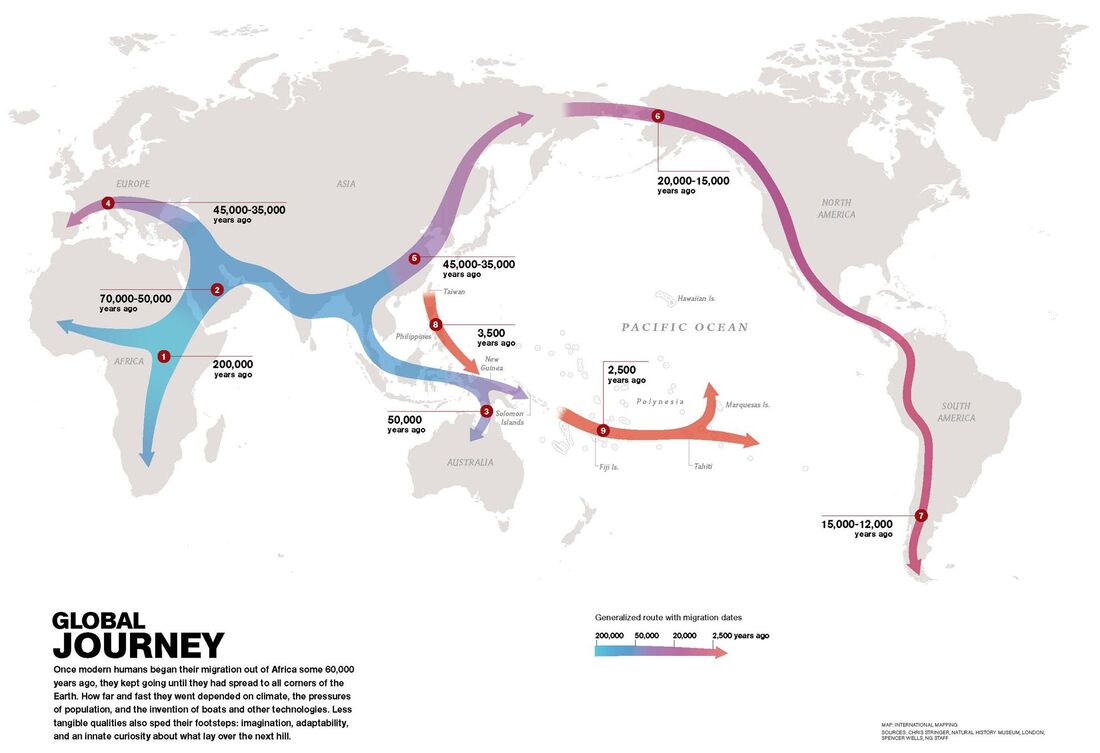

1.1 Big Geography & the Peopling of the Earth

Throughout the Paleolithic era, humans developed sophisticated technologies and adapted to different geographical environments as they migrated from Africa to Eurasia, Australasia, and the Americas.

I. Archaeological evidence indicates that during the Paleolithic era, hunter-forager bands of humans gradually migrated from their origin in East Africa to Eurasia, Australia, and the Americas, adapting their technology and cultures to new climate regions.

I. Archaeological evidence indicates that during the Paleolithic era, hunter-forager bands of humans gradually migrated from their origin in East Africa to Eurasia, Australia, and the Americas, adapting their technology and cultures to new climate regions.

- Humans used fire in new ways: to aid hunting and foraging, to protect against predators, and to adapt to new/colder environments. Humans also developed a wider range of tools specially adapted to different environments from tropics to tundra.

- People lived in small groups that structured social, economic, and political activity. These bands exchanged people, ideas, and goods.

1.2 Neolithic Revolution & Early Agricultural Societies

In response to warming climates at the end of the last Ice Age, from about 10,000 years ago, some groups adapted to the environment in new ways, while others remained hunter-foragers. Settled agriculture appeared in several different parts of the world. The switch to agriculture created a more reliable, but not necessarily more diversified, food supply. Agriculturalists also had a massive impact on the environment through intensive cultivation of selected plants to the exclusion of others, through the construction of irrigation systems, and through the use of domesticated animals for food and for labor. Populations increased; family groups gave way to village life and, later, to urban life with all its complexity. Patriarchy and forced labor systems developed, giving elite men concentrated power over most of the other people in their societies. Pastoralism emerged in parts of Africa and Eurasia. Pastoral peoples domesticated animals and led their herds around grazing ranges. Like agriculturalists, pastoralists tended to be more socially stratified than hunter-foragers. Because pastoralists were mobile, they rarely accumulated large amounts of material possessions, which would have been a hindrance when they changed grazing areas. The pastoralists’ mobility allowed them to become an important conduit for technological change as they interacted with settled populations.

I. Beginning about 10,000 years ago, some human communities adopted sedentism and agriculture, while others pursued hunter-forager or pastoralist lifestyles--different pathways that had significant social and demographic ramifications.

II. Agriculture and pastoralism began to transform human societies.

I. Beginning about 10,000 years ago, some human communities adopted sedentism and agriculture, while others pursued hunter-forager or pastoralist lifestyles--different pathways that had significant social and demographic ramifications.

- The Neolithic Revolution led to the development of more complex economic and social systems.

- People in each region domesticated locally available plants and animals.

- Pastoralism developed at various sites in the grasslands of Afro-Eurasia, affecting the environment in a variety of ways.

- Agricultural communities had to work cooperatively to clear land and create the water control systems needed for crop production, drastically affecting environmental diversity.

II. Agriculture and pastoralism began to transform human societies.

- Pastoralism and agriculture led to more reliable and abundant food supplies, which increased the population.Surpluses of food and other goods led to specialization of labor, including new classes of artisans and warriors, and the development of elites.

- Technological innovations led to improvements in agricultural production, trade, and transportation. (Pottery, Wheels, and wheeled vehicles)

- Patriarchal forms of social organization developed in both pastoralist and agrarian societies.

1.3 Development & Interaction of Early Societies

From about 5,000 years ago, urban societies developed, laying the foundations for the first civilizations. The term civilization is normally used to designate large societies with cities and powerful states. While there were many differences between civilizations, they also shared important features. They all produced agricultural surpluses that permitted significant specialization of labor. All civilizations contained cities and generated complex institutions, such as political bureaucracies, armies, and religious hierarchies. They also featured clearly stratified social hierarchies and organized long-distance trading relationships. Economic exchanges intensified within and between civilizations, as well as with nomadic pastoralists. As populations grew, competition for surplus resources, especially food, led to greater social stratification, specialization of labor, increased trade, more complex systems of government and religion, and the development of record keeping. As civilizations expanded, they had to balance their need for more resources with environmental constraints such as the danger of undermining soil fertility. Finally, the accumulation of wealth in settled communities spurred warfare between communities and/or with pastoralists; this violence drove the development of new technologies of war and urban defense.

|

I. Core foundational civilizations developed in a variety of geographical and environmental settings where agriculture flourished, including Mesopotamia in the Tigris and Euphrates River Valleys, Egypt in the Nile River Valley, Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa in the Indus River Valley, Shang in the Yellow River (Huang He) Valley, the Olmec in Mesoamerica, and the Chavín in Andean South America. II. The first states emerged within core civilizations in Mesopotamia and the Nile Valley.

III. Culture played a significant role in unifying states through laws, language, literature, religion, myths, and monumental art.

|

|

2.1 Development of Religious & Cultural Traditions

As states and empires increased in size and contacts between regions multiplied, religious and cultural systems were transformed. Religions and belief systems provided a bond among the people and an ethical code to live by. These shared beliefs also influenced and reinforced political, economic, and occupational stratification. Religious and political authority often merged as rulers (some of whom were considered divine) used religion, along with military and legal structures, to justify their rule and ensure its continuation. Religions and belief systems could also generate conflict, partly because beliefs and practices varied greatly within and among societies.

|

I. Codifications and further developments of existing religious traditions provided a bond among the people and an ethical code to live by.

II. New belief systems and cultural traditions emerged and spread, often asserting universal truths.

III. Belief systems generally reinforced existing social structures while also offering new roles and status to some men and women.

IV. Other religious and cultural traditions continued and in some paces were incorporated into major religious traditions.

|

2.2 The Development of States & Empires

As the early states and empires grew in number, size, and population, they frequently competed for resources and came into conflict with one another. In quests for land, wealth, and security, some empires expanded dramatically. In doing so, they built powerful military machines and administrative institutions that were capable of organizing human activities over long distances. Also, they created new groups of military and political elites to manage their affairs. As these empires expanded their boundaries, they also faced the need to develop policies and procedures to govern their relationships with ethnically and culturally diverse populations: sometimes to integrate them within an imperial society and sometimes to exclude them. In some cases, these empires became victims of their own successes. By expanding their boundaries too far, they created political, cultural, and administrative difficulties they could not manage. They also experienced environmental, social, and economic problems when they over-exploited their lands and subjects and permitted excessive wealth to be concentrated in the hands of privileged classes.

I. The number and size of key states and empires grew dramatically as rulers imposed political unity on areas where previously there had been competing states. Key states and empires that grew included:

II. Empires and states developed new techniques of imperial administration based, in part, on the success of earlier political forms.

III. Unique social and economic dimensions developed in imperial societies in Afro–Eurasia and the Americas.

IV. The Roman, Han, Persian, Mauryan, and Gupta empires encountered political, cultural, and administrative difficulties that they could not manage, which eventually led to their decline, collapse, and transformation into successor empires or states.

- Southwest Asia: Persian empires

- East Asia: Qin and Han empires

- South Asia: Mauryan and Gupta empires

- Mediterranean region: Phoenicia and its colonies, Greek city-states and colonies, and Hellenistic and Roman empires

- Mesoamerica: Teotihuacan, Maya city-states

- Andean South America: Moche

- North America: Chaco and Cahokia

II. Empires and states developed new techniques of imperial administration based, in part, on the success of earlier political forms.

- In order to organize their subjects, in many regions imperial rulers created administrative institutions, including centralized governments, as well as elaborate legal systems and bureaucracies.

- Imperial governments promoted trade and projected military power over larger areas using a variety of techniques, including issuing currencies; diplomacy; developing supply lines; building fortifications, defensive walls, and roads; and drawing new groups of military officers and soldiers from the location populations or conquered populations.

III. Unique social and economic dimensions developed in imperial societies in Afro–Eurasia and the Americas.

- Imperial cities served as centers of trade, public performance of religious rituals, and political administration for states and empires.

- The social structures of empires displayed hierarchies that included cultivators, laborers, slaves, artisans, merchants, elites, or caste groups.

- Imperial societies relied on a range of methods to maintain the production of food and provide rewards for the loyalty of the elites.

- Patriarchy continued to shape gender and family relations in all imperial societies of this period.

IV. The Roman, Han, Persian, Mauryan, and Gupta empires encountered political, cultural, and administrative difficulties that they could not manage, which eventually led to their decline, collapse, and transformation into successor empires or states.

- Through excessive mobilization of resources, erosion of established political institutions, and economic changes, imperial governments generated social tensions and created economic difficulties by concentrating too much wealth in the hands of elites.

- Security issues along their frontiers, including the threat of invasions, challenged imperial authority.

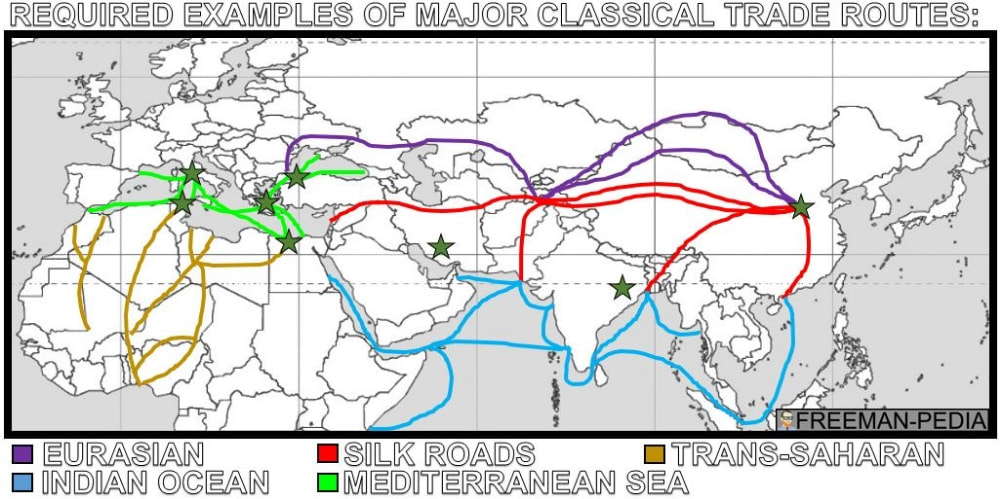

2.3 Emergence of Transregional Trade Networks

With the organization of large-scale empires, the volume of long-distance trade increased dramatically. Much of this trade resulted from the demand for raw materials and luxury goods. Land and water routes linked many regions of the Eastern Hemisphere. The exchange of people, technology, religious and cultural beliefs, food crops, domesticated animals, and disease pathogens developed alongside the trade in goods across far-flung networks of communication and exchange. In the Americas and Oceania, localized networks developed.

I. Land and water routes became the basis for interregional trade, communication, and exchange networks in the Eastern Hemisphere.

II. New technologies facilitated long-distance communication and exchange.

III. Alongside the trade in goods, the exchange of people, technology, religious and cultural beliefs, food crops, domesticated animals, and disease pathogens developed across extensive networks of communication and exchange.

- Many factors, including the climate and location of the routes, the typical trade goods, and the ethnicity of people involved, shaped the distinctive features of a variety of trade routes, including Eurasian Silk Roads, Trans-Saharan caravan routes, Indian Ocean sea lanes, and Mediterranean sea lanes.

II. New technologies facilitated long-distance communication and exchange.

- New technologies permitted the use of domesticated pack animals to transport goods across longer routes.

- Innovations in maritime technologies, as well as advanced knowledge of the monsoon winds, stimulated exchanges along maritime routes from East Africa to East Asia.

III. Alongside the trade in goods, the exchange of people, technology, religious and cultural beliefs, food crops, domesticated animals, and disease pathogens developed across extensive networks of communication and exchange.

- The spread of crops, including rice and cotton from South Asia to the Middle East, encouraged changes in farming and irrigation techniques.

- The spread of disease pathogens diminished urban populations and contributed to the decline of some empires, including the Roman and Han.

- Religious and cultural traditions—including Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism—were transformed as they spread partly as a result of syncretism.